The Constitutional Viability of Five-Month Abortion Laws

This is Issue 9 of the On Point Series.

Abstract: Five-month abortion laws restrict abortion at 20 weeks of pregnancy—when an unborn child can feel pain from abortion. Opponents of five-month abortion laws argue they violate the “viability rule” created by the U.S. Supreme Court. The viability rule provides that government “may not prohibit any woman from making the ultimate decision to terminate her pregnancy before viability.” In most cases viability will occur after 20 weeks of pregnancy. However, the viability rule is unworkable, arbitrary, unjust, poorly reasoned, inadequate, and extreme. The viability rule cannot be justified, especially as applied to five-month laws. In a challenge to a five-month law it is reasonable to conclude that the Court might abandon the viability rule altogether or not apply it to five-month laws.

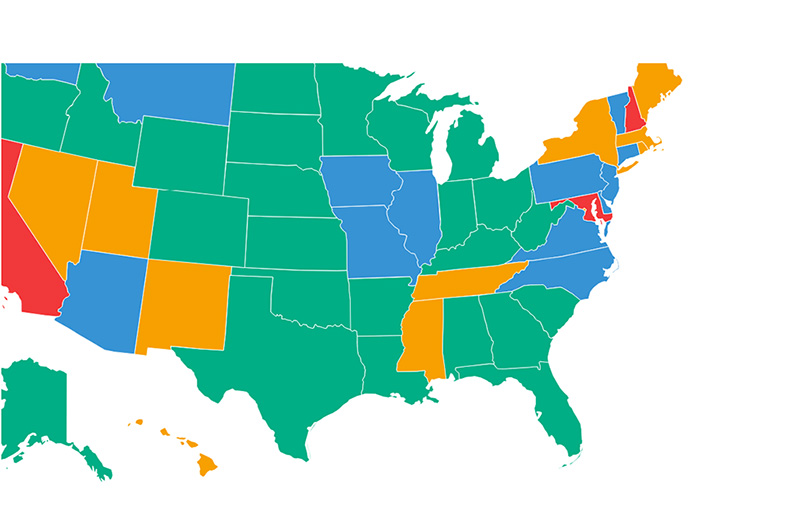

The Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, H.R. 36, would limit abortion at 20 weeks (approximately five months) except when it is necessary to save the life of the mother or where pregnancy has resulted from rape or, in the case of minors, incest.[1] H.R. 36 is based on “substantial medical evidence that an unborn child is capable of experiencing pain at least by 20 weeks after fertilization, if not earlier.”[2] Similar limitations have been adopted in several States and proposed in others.[3]

Opponents argue that limiting abortion at 20 weeks to protect pain-capable unborn children violates what is sometimes called the “viability rule.” The U.S. Supreme Court created the viability rule in the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision and reaffirmed the viability rule in the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision.[4]

The viability rule created by the Court provides that government “may not prohibit any woman from making the ultimate decision to terminate her pregnancy before viability.”[5] Viability can occur at 20 weeks of pregnancy measured from the time of fertilization;[6] however, in the current state of medical technology, viability will occur after the 20-week mark in a very large percentage of cases.[7] Therefore, opponents argue that limiting abortion at 20 weeks to protect pain-capable unborn children violates the viability rule, at least when the restriction applies before viability.[8]

In 2013 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that a State five-month law was unconstitutional because it violated the viability rule.[9] The U.S. Supreme Court chose not to review that decision.[10]

However, there are good reasons to conclude that, if the Court considers a five-month law in a future case, the Court might abandon the viability rule altogether or not apply it to five-month laws.

The Viability Rule Is Unworkable, Arbitrary, Unjust, Poorly Reasoned, Inadequate, and Extreme

There is no denying that, in the landmark 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Court purported to reaffirm the viability rule. The Court stated that “no changes of fact have rendered viability more or less appropriate as the point at which the balance of interests tips.”[11] Further, a joint opinion in Casey authored by Justice Kennedy and two other justices described Roe as “a reasoned statement, elaborated with great care,”[12] described the viability rule as the “most central principle” of Roe and a “rule of law” and “component of liberty” that “we cannot renounce,”[13] and stated that “there is no line other than viability which is more workable.”[14]

However, the Casey Court explained that it was affirming Roe’s central holding “with whatever degree of personal reluctance any of us may have.”[15] Furthermore, the joint opinion authored by Justice Kennedy and two other justices admitted that the issue of viability was “not before us in the first instance.”[16] The joint opinion explained that “[w]e do not need to say whether each of us, had we been Members of the Court when the valuation of the state interest [in the protection of potential life] came before it as an original matter, would have concluded, as the Roe Court did, that its weight is insufficient to justify a ban on abortions prior to viability even when it is subject to certain exceptions.”[17]

Fifteen years later, in the 2007 Gonzales v. Carhart partial-birth abortion case, Justice Kennedy authored a majority opinion for the Court that applied the Casey standards.[18] However, as University of Georgia Law Professor Randy Beck has explained, Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Gonzales “introduced Casey’s standards with the statement ‘[w]e assume the following principles for the purposes of this opinion,’ as if the majority was saving for another day the question of whether the Casey plurality opinion should continue to control.”[19] Professor Beck has published academic articles discussing the viability rule.[20] He goes on to explain that “Justice Kennedy’s opinion [in Gonzales] later referenced ‘the principles accepted as controlling here,’ reinforcing the impression that the majority might not be fully committed to Casey as a final statement of the Court’s position on abortion rights.”[21] Further, Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Gonzales, following his dissent in an earlier partial-birth abortion ban case called Stenberg v. Carhart, highlighted the gruesome and horrific nature of late abortion.[22]

Any doubts Justice Kennedy or other current members of the Court might have about the viability rule would be well placed. The viability rule is extremely flawed and cannot be justified, especially as applied to five-month laws.

The viability rule is unworkable. The viability rule is unworkable as a meaningful regulatory standard due to, in the Court’s words, “the uncertainty of the viability determination.”[23] Professor Beck discusses the 1979 Colautti v. Franklin case in which the Court acknowledged that “the probability of any particular fetus’ obtaining meaningful life outside the womb can be determined only with difficulty.”[24] Further, “different physicians equate viability with different probabilities of survival, and some physicians refuse to equate viability with any numerical probability at all.”[25] Given these “uncertainties,” it is “not unlikely,” the Court explained, “that experts will disagree over whether a particular fetus in the second trimester has advanced to the stage of viability.”[26]

In addition to providing a highly uncertain standard for uniformly determining the legal status of unborn children, in some cases the viability rule will provide a standard of regulation that is difficult if not impossible to enforce.[27]

“The [v]iability [r]ule [i]s [a]rbitrary.”[28] According to Professor Beck, “[t]he Court has never offered an adequate constitutional justification for the viability rule.”[29] Professor Beck argues that the Supreme Court has failed “to explain why the capacity to survive outside the womb should be required as a constitutional matter before a state can protect the life of a second-trimester fetus.”[30] “In an important sense,” Professor Beck writes, “the viable fetus is no more independent of the mother than the previable fetus; both remain in the womb and depend on the mother’s body for survival.”[31] Further, “the viable fetus imposes no less of a burden on its mother than a previable fetus.”[32]

Now-public archival evidence from the Court’s deliberation in Roe reinforces the arbitrary character of the viability rule. “‘This is arbitrary,’” one justice wrote of an eventually discarded proposal to draw the line in Roe at the end of the first trimester, “‘but perhaps any other selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary.’”[33]

Perhaps it is not surprising that an arbitrary rule that was arbitrarily decided would produce arbitrary legal protections. For example, Professor Beck argues that viability could be influenced by factors such as race, gender, whether the mother smokes, the altitude of where the baby and mother live, and access to treatment facilities.[34]

In addition, average viability can change, and has changed, with developments in medical technology. In the 1973 Roe case, the Court stated that, though it “may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks,” viability was “usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks).”[35] Forty years later, in 2013, a federal district court recognized that “23 to 24 weeks gestational age is, on average, the attainment of viability.”[36] As Professor Beck explains, “Due to advances in neonatal care, the state may be able to protect a fetus from abortion today when, just a few years before, it would have been constitutionally disabled from protecting an identical fetus.”[37]

The viability rule is unjust. For many of the same reasons that the viability rule is unworkable and arbitrary, it is also unjust. The viability rule is unjust because it can result in radically different legal protections for unborn children based on factors that should be irrelevant to such a determination.[38] Professor Beck argues that a child’s viability can vary based on factors including race, gender, whether the mother smokes, the altitude of where the baby and mother live, and access to treatment facilities.[39]

The viability rule is also unjust because it hinges the constitutional protections of unborn children on medical judgments that, due to the great uncertainty involved, can be meaningfully regulated only with difficulty if at all. This regulatory difficulty is a problem even if abortion providers operate in good faith. It becomes even more problematic when one considers that the same physician charged with determining whether an unborn child qualifies for legal protections will often have a financial incentive in aborting that child.[40]

The viability rule is poorly reasoned. According to Professor Beck, “scholars from a wide variety of backgrounds have recognized” that “Roe literally provided no argument in favor of treating viability as the controlling line, much less an argument grounded in constitutional principles.”[41] In Professor Beck’s own analysis, “The Court has never offered an adequate constitutional justification for the viability rule.”[42]

Professor Beck further argues that “the Court has not grappled with the duration of abortion rights in a case where the answer mattered to the outcome.”[43] According to Professor Beck, “[t]he Court adopted the viability rule in dicta in Roe and reaffirmed it in dicta in Casey.”[44] He explains, “The Roe litigation involved a challenge to a Texas statute that prohibited all abortions except those necessary to save the mother’s life. . . . The validity of the Texas statute did not turn on the question of when in pregnancy a state may regulate to protect fetal life.”[45] According to Professor Beck, “the Court’s articulation of the viability rule constituted dictum, unnecessary to resolve the case before the Court.”[46] Similarly, according to Professor Beck, “the Pennsylvania regulations at issue in Casey applied from the outset of pregnancy. As a consequence, the reaffirmation of the viability rule in Casey also represented dictum, unnecessary to resolution of the issues before the Court.”[47]

One problem with courts deciding an issue that is unnecessary to resolution of a case is that parties might not develop the record, brief, or argue the issue to the extent or in the same way that they otherwise would do. According to Professor Beck, in Roe “[t]he parties did not address the question of, assuming a right to abortion, how far into pregnancy it extends, and the advocates in oral argument avoided answering such line-drawing questions.”[48] “Since the duration of abortion rights was not at issue in Roe or Doe,” he writes, “the parties did not brief or argue the question, nor did they prepare a record designed to assist the Court in addressing the durational problem.”[49] Similarly, Professor Beck finds that “the parties in Casey did not brief the Court on potential arguments for or objections to the viability rule.”[50] “[S]ince viability was not relevant to the constitutionality of the challenged Pennsylvania regulations,” he writes, “potential justifications for the viability rule played no more than a de minimis role in the parties’ briefs.”[51] The takeaway, in Professor Beck’s words, is that the Court “has never considered the merits of the viability rule based on plenary briefing and argument.”[52]

The viability rule is inadequate to accommodate legitimate government interests. Legislation passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in 2013 found that “there is substantial medical evidence that an unborn child is capable of experiencing pain at least by 20 weeks after fertilization, if not earlier.”[53] The viability rule is inadequate if it cannot accommodate the full range of government interests in regulating abortion.

The viability rule is also inadequate if it forecloses the opportunity for meaningful legislative consideration of abortion-related issues. Professor Beck observes that Justice Kennedy, in a dissenting opinion in the 2000 Stenberg v. Carhart case, “recognized the important role state legislatures play in mediating societal divisions over abortion.”[54] And in Doe the Court referred to the right of the State “to readjust its views and emphases in the light of the advanced knowledge and techniques of the day.”[55] In recent years, more than 10 states have enacted some version of five-month laws,[56] and now the U.S. Congress seeks to do the same. The viability rule is inadequate if it reflexively and unreflectively forecloses legislative efforts to address emerging issues such as fetal pain.

“The [v]iability [r]ule [i]s [e]xtreme.”[57] The viability rule is extreme according to certain measures of public opinion in the United States. A 2014 Quinnipiac poll found that 60% of respondents support legislation that, subject to certain exceptions, would limit abortion at 20 weeks.[58] A 2013 ABC News/Washington Post poll found that 56% of respondents say abortion should be legal without limitations only up to 20 weeks instead of 24 weeks.[59] A 2013 Gallup poll even found that 64% of respondents think abortion should generally be illegal in the second three months of pregnancy.[60]

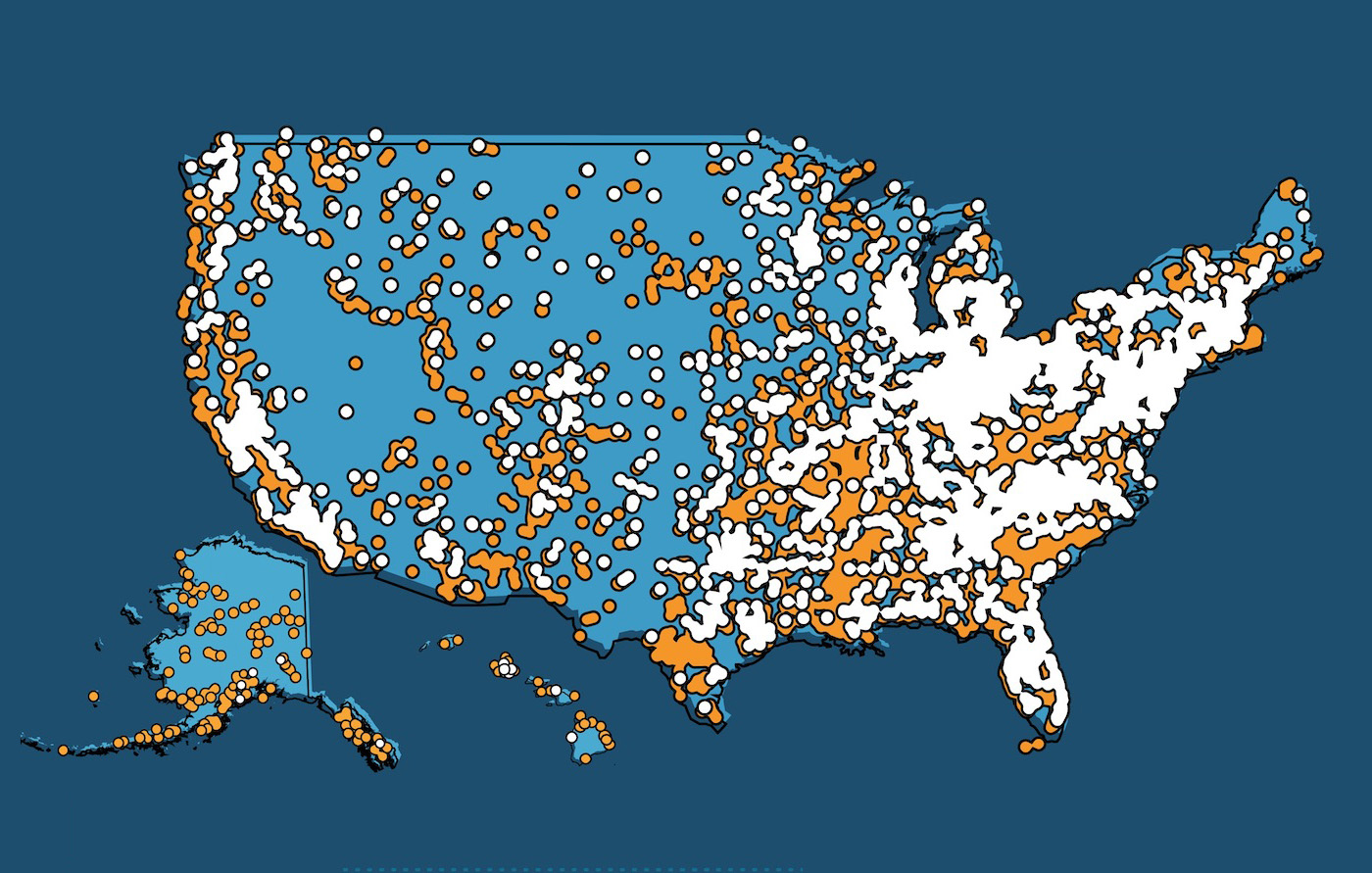

The viability rule is also extreme compared to international norms. A 2014 study published by the Charlotte Lozier Institute found that the United States is one of only seven countries worldwide that permit elective abortion past 20 weeks.[61] This study puts the U.S. in the top 5% of most permissive countries on abortion out of 198 countries analyzed.[62]

The Court can no longer, if it ever could, credibly maintain the viability rule, especially as applied to five-month laws.

The statement of the three justices in the joint opinion in Casey that “there is no line other than viability which is more workable”[63] is flatly unconvincing. A regulatory line “based on a particular gestational age (for example, 20 weeks) is simpler, less debatable, and easier to apply than viability.”[64] A 20-week rule would also “be an easier line for the state to enforce.”[65] “Bright lines make law enforcement easier.”[66]

In 1992 the Court asserted that “no changes of fact have rendered viability more or less appropriate as the point at which the balance of interests tips.”[67] But according to Professor Beck, “In neither Roe nor Casey . . . did the Court exhibit awareness of the racial and gender disparities characterizing fetal viability”[68] and “[n]either case mentioned the role played by irrelevant behavioral and environmental factors.”[69] Furthermore, whatever the state of scientific understanding in 1992 when Casey was decided, more than 20 years later, in 2013, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation finding that “there is substantial medical evidence that an unborn child is capable of experiencing pain at least by 20 weeks after fertilization, if not earlier.”[70]

Nor can the Court assert, as the joint opinion in Casey did in 1992, that Roe’s pronouncement on viability “was a reasoned statement, elaborated with great care.”[71] According to Professor Beck, “[t]he Court has never offered an adequate constitutional justification for the viability rule.”[72] Professor Beck also argues that the Court “has never considered the merits of the viability rule based on plenary briefing and argument in a case where it mattered to the outcome.”[73] The viability rule is poorly reasoned and, as demonstrated by now-public archival evidence, self-consciously arbitrary. It fails to command continued adherence.

In 1992 the joint opinion in Casey explained that the “viability line” “has, as a practical matter, an element of fairness. In some broad sense it might be said that a woman who fails to act before viability has consented to the State’s intervention on behalf of the developing child.”[74] But in “some broad sense” the very same can be said about failure “to act” before 20 weeks (or roughly five months) after fertilization,[75] a time that in many cases will fall more than halfway through pregnancy.

The Casey Court also explained that for two decades people had “organized intimate relationships” and “made choices” “in reliance on the availability of abortion in the event that contraception should fail.”[76] It is unnecessary to address the particular merits of this rationale to observe more generally that replacing viability with 20 weeks would not undermine reliance on abortion as backup contraception.[77] As Professor Beck writes, “Whatever reasonable reliance interests exist in this context can be fully vindicated through an abortion right that ends well before the point of viability.”[78]

In Casey, Justice Kennedy and two other justices declared, “Consistent with other constitutional norms, legislatures may draw lines which appear arbitrary without the necessity of offering a justification. But courts may not. We must justify the lines we draw.”[79] Whether or not it was clear in 1992 it is glaring now—the viability rule cannot be justified, and that’s especially true as applied to five-month laws.

The Court Might Abandon the Viability Rule Altogether or Not Apply It to Five-Month Laws

The viability rule is unworkable, arbitrary, unjust, poorly reasoned, inadequate, and extreme. In a future case involving a five-month law that presents the issue for reconsideration, the U.S. Supreme Court would have many good reasons to abandon the viability rule altogether.

Professor Beck argues that the force of precedent should not bar the Court from reconsidering the viability rule in a future case. He has identified three factors that might weaken the scope or weight accorded to previous judicial decisions. (1) Where a rule was announced in dicta, “meaning that the Court reached beyond its role of resolving the dispute brought to it by the parties and opined on questions unnecessary to the outcome.”[80] (2) Where “the Court has resolved an issue without adequate briefing and argument.”[81] (3) Where an opinion is “inadequa[te]” and fails to explain “the outcome” judges reach.[82]

According to Professor Beck, each of these factors applies to the viability rule.[83] “[T]he Court should not view the viability rule as binding precedent precluding future examination of the duration of abortion rights on the basis of plenary briefing and argument.”[84]

Even if the Court does not abandon the viability rule altogether, the Court might nevertheless choose to constrain the rule in such a way that allows for five-month laws to be upheld. Professor Beck has developed this theory in academic articles.[85] He explains that, if confronted with a challenge to a five-month law, the Court “could appropriately confine” the viability rule “to the state interest the Court designed the rule to cover, a purely moral assessment of the value of unborn human life.”[86] Under this theory, laws advancing different government interests, such as protecting unborn children against pain, could be judged under a different durational rule.

Professor Beck explains that, in the 2007 Gonzales v. Carhart ruling upholding the federal partial-birth abortion ban, the Court recognized “a multiplicity of state interests distinct from the interest in protecting the life of any particular fetus.”[87] He explains that, “[n]otwithstanding the majority’s recognition [in Gonzalez] of these new state interests justifying regulation of abortion, the Gonzales opinion ‘assumed’ that the viability rule would remain the measure of the duration of abortion rights. However,” Professor Beck writes, “there is no particular reason this should be the case, and many reasons to believe it should not.”[88]

Roe’s dicta on the duration of abortion rights took the position that the point at which a particular state interest would justify substantial restrictions on abortion depended on the particular state interest in question. Thus, an interest in promoting maternal health justified regulation at the end of the first trimester, when abortion might present a greater risk to the mother’s health than carrying a child to term. The interest in protecting fetal life justified regulation only at viability, though for reasons the Court did not articulate. Just as the states could assert the distinct interests recognized in Roe at different points in pregnancy, now that Gonzales permits states to advance previously unrecognized interests in support of abortion regulations, there is no reason all of those interests should be subject to the same durational line.

Consider, for example, the state laws passed in a number of jurisdictions forbidding most abortions after twenty weeks of pregnancy on the theory that the fetus can feel pain at that stage of development. Assuming the Court finds prevention of fetal pain to be a legitimate state interest, there seems to be no reason why viability would prove particularly relevant to the permissibility of state laws premised on that interest. There does not appear to be any logical connection between the ability of the fetus to feel pain, which depends more on neurological development, and the ability of the fetus to live outside the womb, which depends more on the development of respiratory capacity. The Court could appropriately confine the viability rule to the state interest the Court designed the rule to cover, a purely moral assessment of the value of unborn human life, and recognize different durational limits for the new state interests now permitted under Gonzales.[89]

Under this approach, not only could the Court uphold a five-month law without abandoning the viability rule, it could do so based on or at least consistent with Roe, the very precedent that created the viability rule.

Professor Beck’s argument about constraining the viability rule to certain state interests is only strengthened by the fact that the issue of fetal pain was not addressed by the Court in either Roe or Casey.

Conclusion

The viability rule is not the only constitutional issue that might be considered in adopting a five-month abortion policy. And in litigation, the viability rule is not the only constitutional issue that might require adjudication.

However, the viability rule is the core constitutional issue presented by five-month laws. The continued validity and scope of the viability rule will likely occupy a central place in any litigation involving five-month laws.

The viability rule is unworkable, arbitrary, unjust, poorly reasoned, inadequate, and extreme. The viability rule cannot be justified, especially as applied to five-month laws. It is reasonable to conclude that, if confronted with the question in a future case, the Court might abandon the viability rule altogether or not apply it to five-month laws.

Key Points:

- The viability rule is unworkable, arbitrary, unjust, poorly reasoned, inadequate, and extreme.

- The viability rule cannot be justified, especially as applied to five-month laws.

- It is reasonable to conclude that in a legal challenge to a five-month law the Court might abandon the viability rule.

- Even if the Court does not abandon the viability rule the Court might not apply the rule to five-month laws.

Thomas M. Messner is Senior Fellow in Legal Policy at the Charlotte Lozier Institute.

[1] Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, H.R. 36, 114th Cong. § 3(a) (2015), available at https://www.congress.gov/114/bills/hr36/BILLS-114hr36ih.pdf.H.R. 36, § 3(a). An identical bill was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in 2013. See Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, H.R. 1797, 113th Cong. (2013), available at https://www.congress.gov/113/bills/hr1797/BILLS-113hr1797rfs.pdf. See also Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act, S. 1670, 113th Cong. (2013), available at https://beta.congress.gov/113/bills/s1670/BILLS-113s1670is.pdf;

[2] H.R. 36, § 2(11). See also H.R. 1797, 113th Cong. § 2(11) (2013); S. 1670, 113th Cong. § 2(11) (2013); Brief for the States of Ohio, Montana, and 14 Other States as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners at 3 – 6, Horne v. Isaacson, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014) (No. 13-402), 2014 WL 102430 (cert. denied) [hereinafter Brief for the States] (discussing the “growing body of evidence” suggesting that “an unborn child can suffer pain by twenty weeks’ gestation”).

[3] Guttmacher Institute, State Policies in Brief: State Policies on Later Abortions (Jan. 1, 2015), http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_PLTA.pdf. See Brief for the States, supra note 2, at 6 (asserting that, “[i]n addition to Arizona, twelve other States have passed legislation seeking to further the same interests that Arizona’s law does” and “[s]everal more States are presently considering similar legislation”). Compare id., with Guttmacher Institute, supra (setting forth findings regarding state abortion legislation and denoting laws “[b]ased on the assertion that the fetus can feel pain at 18 or 20 weeks postfertilization”).

[4] Planned Parenthood of Se. Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 846 (1992); Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 163 – 64 (1973).

[5] Casey, 505 U.S. at 879 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[6] Twenty weeks can be measured in different ways including from the first day of the last menstrual cycle (LMP) and from the time of fertilization. The District of Columbia Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act: Hearing on H.R. 3803, Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 112th Cong. 65 (2012) [hereinafter Hearing on H.R. 3803] (Testimony of Colleen A. Malloy, M.D., Assistant Professor, Division of Neonatology/Department of Pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine), available at http://judiciary.house.gov/_files/hearings/printers/112th/112-118_74261.PDF; Guttmacher Institute, supra note 3; Betsy Johnson, Momentum for Late-Term Abortion Limits, Charlotte Lozier Institute (Aug. 5, 2013), http://www.lozierinstitute.org/momentum-for-late-term-abortion-limits/. “The LMP age is the post-fertilization age, plus two weeks.” Hearing on H.R. 3803, supra, at 65. See statistics on survival to one year of life of live-born infants at id., 65 – 66.

[7] See Isaacson v. Horne, 884 F. Supp. 2d 961, 968 (D. Ariz. 2012) (recognizing that “23 to 24 weeks gestational age is, on average, the attainment of viability”), rev’d, 716 F.3d 1213 (9th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014); Hearing on H.R. 3803, supra note 6, at 65 – 66.

[8] See Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants at 8, 5, Isaacson v. Horne, 716 F.3d 1213 (9th Cir. 2013) (No. 12‑16670), 2012 WL 3911687, at *8, *5 (stating that “[t]here is . . . no dispute that the Act prohibits . . . abortions in instances in which the fetus is not viable” and “[n]o other fact is relevant to the merits of the Physicians’ single claim” that “the Act violates the Fourteenth Amendment rights of women seeking to terminate pre-viable pregnancies at or after 20 weeks”).

[9] See Isaacson v. Horne, 716 F.3d 1213, 1225 (9th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014) (stating that the State “ban on abortion from twenty weeks necessarily prohibits pre-viability abortions” and “is therefore, without more, invalid”). See also Guttmacher Institute, supra note 3 (reporting litigation outcome of Arizona law and stating that “[a] new Georgia law that would ban abortion at 20 weeks postfertilization is only being enforced against postviability abortions” and “[a]n Idaho law that bans abortion at 20 weeks postfertilization is enjoined pending the outcome of litigation”); Press Release, American Civil Liberties Union, State Court Temporarily Halts Georgia Abortion Ban (Dec. 24, 2012) (discussing litigation involving Georgia 20-week law), https://www.aclu.org/reproductive-freedom/state-court-temporarily-halts-georgia-abortion-ban.

[10] Horne v. Isaacson, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014) (denying cert. in 716 F.3d 1213 (9th Cir. 2013)).

[11] Casey, 505 U.S. at 861.

[12] Id. at 870 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[13] Id. at 871.

[14] Id. at 870. In Casey Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter authored a joint opinion. Justice Stevens and Justice Blackmun joined certain parts of the joint opinion. See id. at 922 (opinion of Justice Stevens, concurring in part and dissenting in part) (stating that “while I disagree with Parts IV, V-B, and V-D of the joint opinion, I join the remainder of the Court’s opinion”); id. at 922 (opinion of Justice Blackmun, concurring in part, concurring in the judgment in part, and dissenting in part) (stating that “I join Parts I, II, III, V-A, V-C, and VI of the joint opinion . . .”). Notwithstanding whatever precedential value flows from any opinion or section of any opinion in the Casey case, this paper uses the term joint opinion to refer to those parts of the joint opinion joined only by Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter. This practice clarifies where the joint opinion reflects the stated opinions of only those three justices.

[15] Id. at 861 (opinion of the Court).

[16] Id. at 871 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[17] Id.

[18] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

[19] Randy Beck, State Interests and the Duration of Abortion Rights, 44 McGeorge L. Rev. 31, 52 (2013) (citing Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 146 (2007)).

[20] See id.; Randy Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey: Rethinking Viability, 75 UMKC L. Rev. 713 (2007) [hereinafter The Essential Holding of Casey]; Randy Beck, Fueling Controversy, 95 Marq. L. Rev. 735 (2012) [hereinafter Fueling Controversy]; Randy Beck, Gonzales, Casey, and the Viability Rule, 103 Nw. U. L. Rev. 249 (2009) [hereinafter The Viability Rule]; Randy Beck, Self-Conscious Dicta: The Origins of Roe v. Wade’s Trimester Framework, 51 Am. J. Legal Hist. 505 (2011) [hereinafter Self-Conscious Dicta]; Randy Beck, Transtemporal Separation of Powers in the Law of Precedent, 87 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1405, 1458 – 64 (2012) [hereinafter Transtemporal Separation of Powers].

[21] Beck, supra note 19, at 52 (citing Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 156 (2007)).

[22] See Gonzales, 550 U.S. at 135 – 36 (describing “[t]he surgical procedure referred to as ‘dilation and evacuation’ or ‘D & E’” and explaining that it is “the usual abortion method” in the second trimester); Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914, 958 – 59 (2000) (Kennedy, J., dissenting) (discussing “the D & E procedure”).

[23] Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379, 395 (1979).

[24] Colautti, 439 U.S. at 396. See Beck, supra note 19, at 37 (discussing Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379 (1979)).

[25] Colautti, 439 U.S. at 396.

[26] Id.

[27] See Randy Beck, Overcoming Barriers to the Protection of Viable Fetuses, 71 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1263, 1268 – 90 (2014) (discussing difficulties of enforcing regulations that hinge on the viability rule).

[28] Beck, supra note 19, at 37.

[29] Id. at 32. See also Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 280 (arguing that “[t]o date, the Court has failed to offer any theory showing why the Constitution prevents a legislature from protecting fetal life until the fetus can survive outside the womb”).

[30] Beck, supra note 19, at 33.

[31] Id. at 47.

[32] Id. at 40.

[33] Id. at 35 (quoting Memorandum from Justice Harry A. Blackmun to the Conference Re: No. 70-18-Roe v. Wade (Nov. 21, 1972), in Harry A. Blackmun Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Box 151, Folder 6 (on file with the McGeorge Law Review)). See generally Beck, Self-Conscious Dicta, supra note 20 (discussing internal documents related to the Roe decision).

[34] See Beck, supra note 19, at 39 – 40; Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 259 – 61.

[35] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 160 (1973).

[36] Isaacson v. Horne, 884 F. Supp. 2d 961, 968 (D. Ariz. 2012), rev’d, 716 F.3d 1213 (9th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014).

[37] Beck, supra note 19, at 38 – 39. See Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 257 – 58. See also Casey, 505 U.S. at 860 (stating in 1992 that “[w]e have seen how time has overtaken some of Roe’s factual assumptions . . . advances in neonatal care have advanced viability to a point somewhat earlier”).

[38] See Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 258 – 59.

[39] See id. at 259 – 61; Beck, supra note 19, at 39 – 40.

[40] See Brief for the Center for Arizona Policy as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners 15, Horne v. Isaacson, 134 S. Ct. 905 (2014) (No. 13-402), 2014 WL 102430 (cert. denied) [hereinafter Brief for Center for Arizona Policy]; Beck, supra note 27, at 1274 – 75.

[41] Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 267. See also id. at 268 – 69 (asserting that “there is broad academic agreement that Roe failed to provide an adequate explanation for the viability rule” and quoting several sources).

[42] Beck, supra note 19, at 32 (emphasis added). See Beck, The Viability Rule, supra note 20, at 280 (asserting that, “[t]o date, the Court has failed to offer any theory showing why the Constitution prevents a legislature from protecting fetal life until the fetus can survive outside the womb”).

[43] Beck, supra note 19, at 33. See Beck, Self-Conscious Dicta, supra note 20, at 513 – 26.

[44] Beck, supra note 19, at 33.

[45] Beck, Transtemporal Separation of Powers, supra note 20, at 1460.

[46] Id.

[47] Id. at 1463. See Beck, Fueling Controversy, supra note 20, at 740.

[48] Beck, Transtemporal Separation of Powers, supra note 20, at 1462.

[49] Beck, Fueling Controversy, supra note 20, at 743 – 44.

[50] Beck, Transtemporal Separation of Powers, supra note 20, at 1463.

[51] Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 718.

[52] Beck, supra note 19, at 60.

[53] H.R. 1797, 113th. Cong. § 2(11). See also H.R. 36, 114th Cong. § 2(11); S. 1670, 113th Cong. § 2(11).

[54] Beck, supra note 19, at 50.

[55] Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179, 191 (1973).

[56] Johnson, supra note 6.

[57] Beck, supra note 19, at 40. In arguing that the viability rule is extreme, Professor Beck discusses both domestic public opinion and international legal norms. Id. at 40 – 41. This paper includes the same two arguments.

[58] Poll, Quinnipiac University, American Voters Split on Obama’s Immigration Move, Quinnipiac University National Poll Finds; President’s Approval Near All-Time Low, (Nov. 25, 2014), http://www.quinnipiac.edu/images/polling/us/us11252014_uh2ddgk.pdf.

[59] ABC News/Washington Post Poll: Abortion, Majority Supports Legal Abortion, But Details Indicate Ambivalence (July 25, 2013), http://www.langerresearch.com/uploads/1150a4Abortion.pdf.

[60] Lydia Saad, Majority of Americans Still Support Roe v. Wade Decision, Gallup Politics (Jan. 22, 2013), http://www.gallup.com/poll/160058/majority-americans-support-roe-wade-decision.aspx.

[61] Angelina Baglini, Gestational Limits on Abortion in the United States Compared to International Norms, Charlotte Lozier Institute (Feb. 24, 2014), http://www.lozierinstitute.org/internationalabortionnorms/.

[62] Id.

[63] Planned Parenthood of Se. Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 870 (1992) (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[64] Beck, supra note 19, at 48. See also id. at 57 (arguing that even if one accepts that Roe has not proven unworkable “with respect to the basic constitutional right to an abortion, one can make a much stronger argument that viability constitutes an unworkable line if the goal is to enforce state regulations of late-term abortions”). A regulatory line based on 20 weeks of pregnancy “would be easier to ascertain and subject to fewer disagreements among medical professionals than a regulatory line based on fetal viability.” Beck, supra note 27, at 1293.

[65] Beck, supra note 27, at 1293.

[66] Id. at 1291.

[67] Casey, 505 U.S. at 861.

[68] Beck, supra note 19, at 59.

[69] Id. at 60.

[70] H.R. 1797, 113th. Cong. § 2(11). See Brief for the States, supra note 2, at 3 – 6 (discussing the “growing body of evidence” suggesting that “an unborn child can suffer pain by twenty weeks’ gestation”).

[71] Casey, 505 U.S. at 870 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[72] Beck, supra note 19, at 32.

[73] Id. at 60.

[74] Casey, 505 U.S. at 870 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter).

[75] See Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 735 (stating that “[i]t could just as easily be said that a woman implicitly ‘consent[s] to state intervention on behalf of the developing child’ if she fails to act within some shorter period that affords an opportunity to learn of the pregnancy”).

[76] Casey, 505 U.S. at 856.

[77] See Beck, supra note 19, at 58; The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 720.

[78] Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 720.

[79] Casey, 505 U.S. at 870 (joint opinion of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter). See Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 724 – 25; Beck, supra note 19, at 46.

[80] Beck, Transtemporal Separation of Powers, supra note 20, at 1411.

[81] Id.

[82] Id.

[83] Id. at 1460 – 64.

[84] Id. at 1464. But see Casey, 505 U.S. at 854 –61 (identifying factors to use in reexamining a prior holding and applying those factors); id. at 861 – 69 (further discussing the issue of stare decisis and concluding that it was “imperative to adhere to the essence of Roe’s original decision”).

[85] Beck, supra note 19, at 54 – 56; Beck, The Essential Holding of Casey, supra note 20, at 738 – 39.

[86] Beck, supra note 19, at 56.

[87] Id.

[88] Id.

[89] Id. at 55 – 56 (emphases added).